Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Whether you’re just starting out on a journey to a healthy lifestyle, are actively trying to lose weight, or just remember a handful of lessons from school health class, you’ve likely heard the term BMI. In case you need a refresher–what is BMI? BMI stands for Body Mass Index, and it’s a screening tool used by healthcare providers to determine a person’s goal weight range using height and weight. It’s considered the go-to screening tool because it’s simple and non-invasive.

However, BMI is not without its problems. Many healthcare providers, researchers, and even the Centers for Disease Control And Prevention (CDC) have noted some issues with using BMI as a sole indicator of health, or as a diagnostic tool. Additionally, research used to back BMI leaves much to be desired (more on this later). For these reasons, BMI is just considered one small part of your overall health, and not the final word in body weight management.

But if you’re still curious about BMI, how it’s calculated, and what it means for your health, continue reading. We’ll get into the nitty-gritty of this number and what it means for you.

What is BMI: the basics

BMI is a tool used by healthcare providers to assess if people have overweight or obesity. According to the CDC, it’s calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. While many people use it as an indicator of body fatness, it actually measures excess weight, and not excess fat (CDC, n.d.). This is part of why some people consider it an imperfect screening tool — but we’ll get to that.

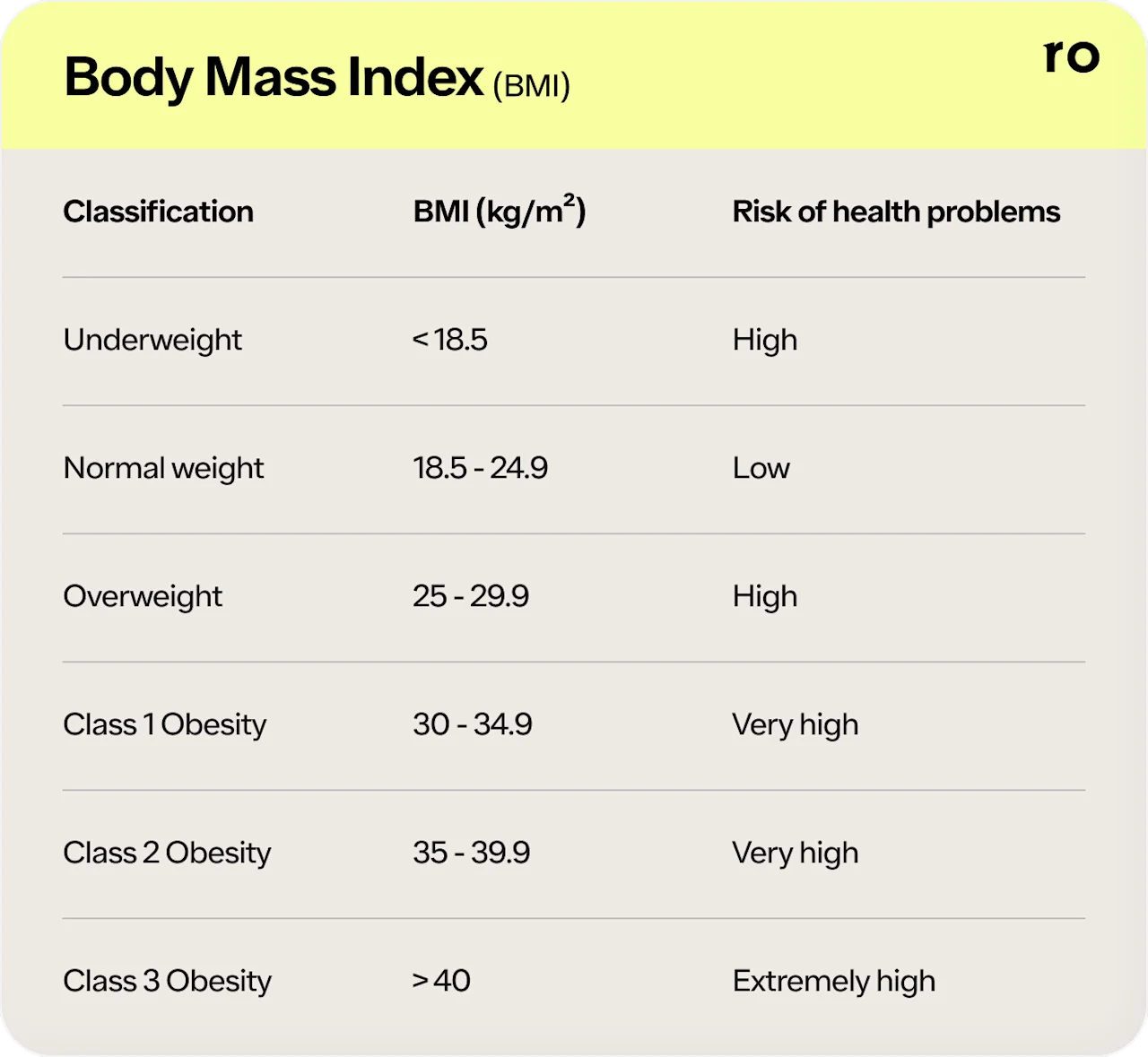

BMI measurements are broken down into four categories: normal, underweight, overweight, and obese. Normal weight in adults is classified as a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9. Underweight is classified by a BMI of under 18.5, while overweight is classified by a BMI of between 25 and 29.9. A BMI of over 30 is classified as obese. Obesity is then frequently broken up into classes: Class 1 is BMI of 30 to 34, Class 2 is BMI of 35 to 39, and Class 3 is BMI of 40 or higher. Class 3 is also categorized as “extreme” or “severe” obesity (CDC, 2022).

While BMI is considered only part of your overall health, some research suggests that a high BMI is associated with health risks. These risks include type 2 diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, certain cancers, chronic back pain (Gutin, 2017), and more health conditions.

While you can calculate your BMI on your own, a BMI calculator is provided below, and the CDC also provides BMI calculators for adults, children, and teens. That said, it’s important to remember that your BMI doesn’t tell the full story of your health. Speak to a healthcare provider to better understand your health status and learn tips for improving your lifestyle.

Find out how much you could lose

Provide your biometric data to get started.

0.0

Your BMI

Underweight

< 18.5

Healthy weight

18.5 - 24.9

Overweight

24.9 - 29.9

Obesity

> 30

Problems with BMI

While some believe BMI is a good indicator of high body fat, it’s not without its limitations. Factors like age, sex, ethnicity, and muscle mass can influence the relationship between BMI and body fat. It also doesn’t consider bone mass, nor does it provide any indication of how fat is distributed among individuals (Nuttall, 2015).

For example, athletes with a lot of muscle may find that their BMI might be high, but their body fat percentages might be low or normal. Since BMI doesn’t take muscle into account, it could classify a person with low body fat as having overweight or obesity. And while BMI is associated with health problems, it’s important to remember that high body fat is the factor that most higher risk health issues are connected to.

These misclassifications go both ways, too. Research suggests that BMI may underestimate the prevalence of obesity in the general population, especially when you look at actual body fat percentages (Nuttall, 2015).

Racial discrimination in the study of BMI offers more arguments against the use of this screening tool. The majority of data used to back BMI is from white populations. But different races and ethnicities gain weight and respond to weight gain differently. For example, research suggests that weight gain may be particularly detrimental in Asian populations, which is why some advocate for lower BMI ranges for obesity in these ethnic groups (Shai, 2006).

BMI also fails to account for biological sex and age. Because of their body compositions, biological women tend to have greater amounts of total body fat than men with equal BMIs. Older adults also tend to have more body fat than younger adults, even if their BMIs are equivalent (Nuttall, 2015).

BMI is calculated the same way for children as it is for adults. But it should be interpreted differently. For children and adolescents between the ages of 2 and 20, BMI is relative to a person’s age and sex. That’s because the amount of body fat changes dramatically with age. For children, anything less than the 5th percentile is considered underweight, where a percentile between 5th and 84th is considered a healthy weight. The 85th percentile to the 94th percentile is considered overweight, and anything equal or greater than the 95th percentile is considered obese (CDC, 2022).

Other measures of body fat

Your BMI is not the only option to measure body fat. Other methods range from skinfold thickness measuring, to waist circumference measuring, to underwater weighing.

The most accurate way to assess your body fat percentage is the dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) test. In this test, x-ray beams measure your density at different parts of your body.

The issue with these tests, however, is that they can be invasive, expensive, or just not widely available. That’s why, although flawed, BMI tends to be the go-to for healthcare providers—it’s an easy way to screen for body fat.

That said, BMI should not be used as a diagnostic tool for weight loss. Instead, it should be used as a screening tool to identify potential weight problems. A healthcare provider can then provide medical advice from there. Other factors, like evaluations of diet, physical activity, family history, and other health screenings, should be taken along with BMI to get the full story of a person’s health.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (n.d.). Body Mass Index: Considerations for Practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/BMIforPactitioners.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Assessing your weight. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/index.html

Gutin, I. (2017). In BMI we trust: reframing the body mass index as a measure of health. Social Theory & Health, 16 (3), 256–271. doi: 10.1057/s41285-017-0055-0. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31007613/

Nuttall, F. Q. (2015). Body Mass Index: obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutrition today, 50 (3), 117–128. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000092. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4890841/

Pasco, J. A., Holloway, K. L., Dobbins, A. G., et al. (2014). Body mass index and measures of body fat for defining obesity and underweight: a cross-sectional, population-based study. BMC Obesity, 1 (1). doi: 10.1186/2052-9538-1-9. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26217501/

Shai, I., Jiang, R., Manson, J. E., et al. (2006). Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care, 29 (7), 1585–1590. doi:10.2337/dc06-0057. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16801583/