Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Diaphoresis is excessive sweating that is not due to the temperature around you or physical exertion, but an underlying medication condition. Another term for diaphoresis is secondary hyperhidrosis. Hyperhidrosis is a condition where you have excessive sweating; secondary refers to the fact that the sweating is secondary to a separate medical condition or is the side effect of a medication. Diaphoresis, or secondary hyperhidrosis, is different from primary hyperhidrosis; primary hyperhidrosis is excessive sweating that is not caused by a medical condition or medication side effect.

In diaphoresis, you sweat more than average without the usual triggers, like external temperature or exercise. Often, sweating occurs in large areas of your body, rather than only in specific areas, like the palms of your hands or soles of your feet. Secondary hyperhidrosis also usually starts in adulthood and may occur at night as well as during the day (Nawrocki, 2019).

What are the potential causes of diaphoresis?

There is a broad range of conditions that can cause profuse sweating.

Hormonal causes

Hormone abnormalities are common causes of diaphoresis, and include menopause, hyperthyroidism, pregnancy, diabetes, and endocrine tumors.

Menopause: Episodes of excessive sweating, during both day and night, are frequent in women going through menopause, or those near menopause (perimenopause), due to hormonal changes; these are commonly known as "hot flashes" or if occurring at night, "night sweats." For women around age 50 having irregular or absent periods along with episodes of sweating, menopause is the most likely cause of their hyperhidrosis. Up to 80% of women in menopause report some symptoms of diaphoresis; symptoms can begin years before the periods stop (Harlow, 2020). The profuse sweating may be due to a dysregulation of the hypothalamus (a gland in the brain that acts as the thermostat of the body) caused by a decrease in estrogen levels (Paisley, 2010). However, if there are other symptoms present, like coughing, fever, or lymph node enlargement, your provider may need to perform additional testing.

Thyroid abnormalities: Thyroid disorders, especially an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism), can lead to diaphoresis. When your thyroid is overactive, it releases too much thyroxine, which increases your metabolism and leads to diaphoresis. Common symptoms that may point to hyperthyroidism are a racing heartbeat (palpitations), shaking hands, nervousness, weight loss, and a change in your eye appearance.

Pregnancy: Pregnancy and its associated hormonal changes can lead to excessive sweating.

Diabetes: People with diabetes sometimes have low blood sugar, also called hypoglycemia. When this happens, your body activates the fight-or-flight response, which can also cause profuse sweating. These dips may occur at night, leading to night sweats (Viera, 2003). Accompanying symptoms that may suggest that you are having an episode of low blood sugar include dizziness, anxiety, loss of vision, extreme fatigue, and blurry vision. Hypoglycemia, if left untreated, can be life-threatening, and you must restore your blood sugar levels quickly.

Endocrine tumors: Tumors that produce excess hormones, like pheochromocytoma and carcinoid tumor/carcinoid syndrome, can cause hyperhidrosis by affecting the normal balance of hormones.

Infections

Another potential cause of excessive sweating are infections; common infections that cause this are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), tuberculosis (TB), infections of the lining of the heart (endocarditis), and bone infections (osteomyelitis) (Walling, 2011). Common symptoms of infection include fever, chills, and cough.

Heart attack

One of the classic signs of a heart attack (myocardial infarction) is diaphoresis. Other warning signs are chest pain/pressure/squeezing sensation, shortness of breath, paleness, nausea, anxiety, and pain in the arms, neck, back, or jaw. Heart attacks are a medical emergency; if you experience any of these symptoms, seek medical attention immediately.

Substance withdrawal

Withdrawal in people who abuse certain substances, like alcohol and benzodiazepines, can cause diaphoresis.

Cancer

Certain cancers, like leukemia and lymphoma, can have profuse sweating; these conditions also have other signs and symptoms like unexplained weight loss, fatigue, and lymph node enlargement.

Anaphylaxis

People who experience anaphylaxis have extreme allergic reactions to triggers, such as bee stings, peanuts, shellfish, etc. During anaphylaxis, common symptoms include diaphoresis, shortness of breath, anxiety, itching, hives, a drop in blood pressure, and in severe cases, loss of consciousness and death. Anaphylaxis is a medical emergency; if you experience these symptoms, seek medical attention immediately.

Other medical conditions

Other medical conditions that can cause diaphoresis: gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), anxiety disorders, autoimmune disorders (like rheumatoid arthritis and giant cell arteritis, obesity, sleep disorders (like obstructive sleep apnea), and stroke (Mold, 2012).

Medications

As mentioned previously, some medicines have profuse sweating as their side effect, including (McConaghy, 2018):

Antidepressants, like venlafaxine (see Important Safety Information) and fluoxetine (see Important Safety Information)

Diabetes medications, like insulin, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones

Hormone therapy, like raloxifene and tamoxifen

Drugs used to treat fevers (antipyretics) like acetaminophen and aspirin

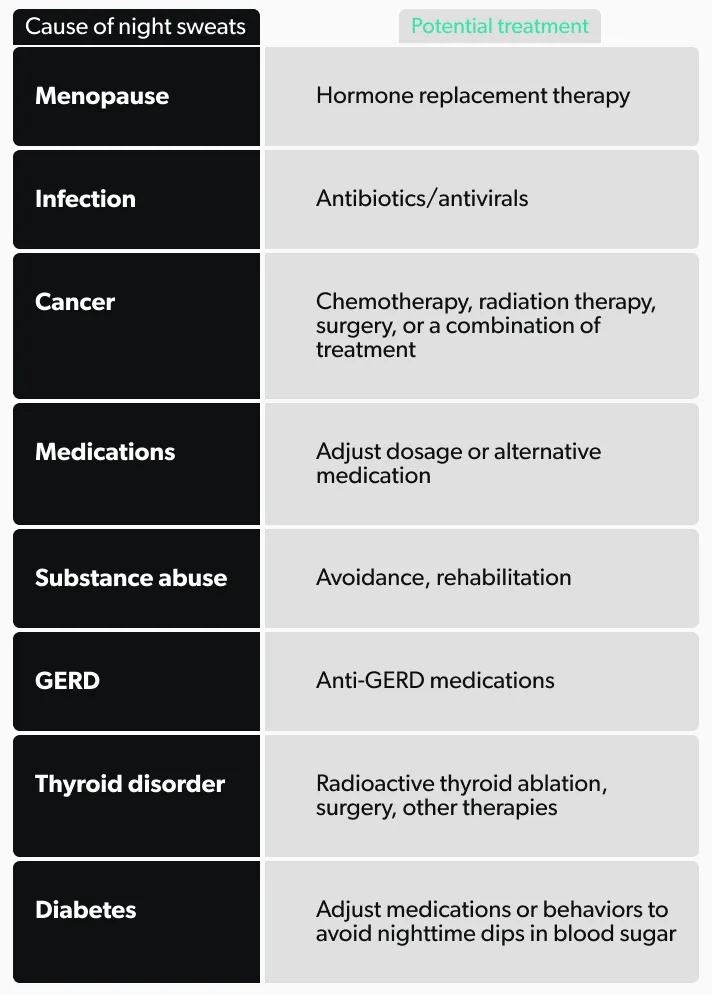

Treatment of diaphoresis

The best way to decrease diaphoresis is to find the underlying condition and treat it. Some potential treatment options, depending on some of the common causes of diaphoresis, are the following:

If medication side effects are the cause of your hyperhidrosis, then changing the dose or switching to an alternative drug may improve your sweating. However, in cases where that is not possible, there are other options to treat the diaphoresis, including:

Prescription-strength antiperspirant with aluminum chloride: One example is Drysol. This antiperspirant gets into and plugs the sweat glands, sending signals to stop your body from producing sweat

Iontophoresis: Immersing your hands or feet in tap water while a medical device sends a low-voltage electric current through the water to shut down the sweat glands

Anticholinergic meds: Examples include oxybutynin and glycopyrrolate. These pills prevent stimulation of sweat glands

Botulinum toxin (brand name Botox) injections: Temporarily prevents the stimulation of sweat glands in affected areas

Simple behavioral modifications like adjusting sleep habits may help, regardless of the cause, including:

Wearing shoes and socks made of natural materials that allow your feet to breath

Wearing loose-fitting clothes made of natural or moisture-wicking fabrics

Applying absorbent powder to areas that sweat

Can you prevent diaphoresis?

There is no real way to prevent diaphoresis; however, some of the medical conditions that cause it may be preventable. Exercise, eating right, and managing your blood sugars can help with diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. If you have profuse sweating, wear loose-fitting, breathable clothes and make sure to hydrate. You should talk to your healthcare provider about any changes in your sweating patterns.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Harlow, S. D., Elliott, M. R., Bondarenko, I., Thurston, R. C., & Jackson, E. A. (2020). Monthly variation of hot flashes, night sweats, and trouble sleeping. Menopause, 27 (1), 5–13. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001420, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31567864

McConaghy, J. R., & Fosselman, D. (2018). Hyperhidrosis: Management Options. American Family Physician, 97 (11), 729–734. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2018/0601/p729.html#afp20180601p729-b21

Mold, J. W., Holtzclaw, B. J., & Mccarthy, L. (2012). Night Sweats: A Systematic Review of the Literature. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25 (6), 878–893. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.120033, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23136329

Nawrocki, S., & Cha, J. (2019). The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 81 (3), 657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.071, https://www.nc b i.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30710603

Paisley, A. N., & Buckler, H. M. (2010). Investigating secondary hyperhidrosis. BMJ, 341 , c4475. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4475, https://www.ncbi. n lm.nih.gov/pubmed/20829299

Viera, A. J., Bond, M. M., & Yates, S. W. (2003). Diagnosing Night Sweats. American Family Physician, 67 (5), 1019–1024. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12643362

Walling, H. W. (2011). Clinical differentiation of primary from secondary hyperhidrosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 64 (4), 690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21334095