Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Unfortunately, “free testosterone” does not mean testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) at no cost (and you should be very wary of anyone making that offer).

Most of the testosterone in your body is bound to proteins. However, free testosterone is unattached and flows freely through your veins. When a healthcare provider tests your testosterone levels with a blood test, they may test your total testosterone levels and your free testosterone levels. They’re both important.

Continue reading to learn more about free testosterone levels and what they mean for your health.

What is free testosterone?

Most people are familiar with testosterone, but you might not know that you have both “bound testosterone” and “free testosterone.”

Most of the testosterone in your body is attached to one of two proteins: albumin and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). However, about 2–5% of the testosterone in your body is unattached, otherwise known as “free” testosterone. Free testosterone and testosterone bound to albumin are easily used by the body—they are also called bioavailable testosterone (Antonio, 2016).

Total testosterone is a measure of both free and bound testosterone, and the sex hormone plays a vital role in the following body functions (Nassar, 2022):

Growth of facial and body hair

Producing sperm

Regulating mood

Maintaining muscle mass and bone density

Producing red blood cells

Where does testosterone come from?

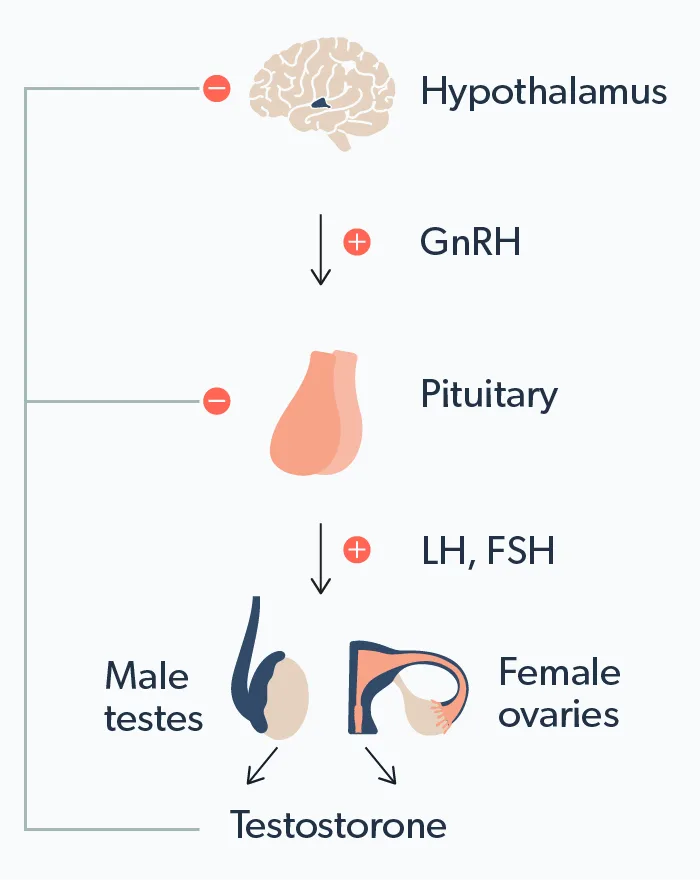

As with most hormonal pathways in the body, testosterone production is complex. The process looks something like this:

Let’s break that down into steps:

A part of your brain called the hypothalamus releases the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH).

GnRH tells the pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH) into your bloodstream.

In biological men, when LH reaches the testicles through the blood, it stimulates special cells in the testes, called Leydig cells. These Leydig cells are ultimately responsible for producing testosterone. In biological women, specialized cells in the ovaries called theca cells make testosterone.

As serum testosterone levels rise, the brain sends signals to the pituitary gland and hypothalamus to stop stimulating testosterone production.

It sounds complex, but this feedback loop is the body’s way of naturally regulating your hormones.

Why test for free testosterone?

Many people are concerned about their testosterone levels. Testosterone levels naturally decrease over time, with studies showing that testosterone levels begin dropping around age 35 and continue to decline each year (Handelsman, 2015). Low testosterone in and of itself is not necessarily a problem.

However, some people may develop symptoms indicating a testosterone deficiency (also called hypogonadism or low T). Up to 12% of men overall and up to 50% of men over the age of 80 may experience testosterone deficiency (Zarotsky, 2014; Snyder, 2020).

If you experience symptoms of low testosterone—like fatigue, low libido, and depression—make an appointment with your healthcare provider and have your testosterone levels checked. Be sure to request a blood test that measures both your free testosterone levels and total testosterone levels—many providers will measure total testosterone without testing free testosterone levels. Free testosterone levels may fall faster than your total testosterone concentration—all the more reason to test your free testosterone levels (Snyder, 2020).

Some people may have “normal” total testosterone levels but low free testosterone—so if you only test for one and not the other, you and your provider may not be getting the whole picture (Antonio, 2016).

What are normal free testosterone levels?

It’s difficult to define “normal”—this is especially true for free testosterone. Most often, when people talk about testosterone levels, they are referring to total testosterone.

Normal testosterone levels run in the range of 300–1000 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dL). This number can vary daily from morning to evening, so providers typically check total testosterone levels between 8 a.m. and 10 a.m. on two different days. Levels below 300 ng/dl on both mornings classifies as low T (Sizar, 2022).

In contrast, free testosterone is difficult to measure directly. Most laboratories use an equation to indirectly measure your free testosterone levels based on your total testosterone and other values. The “normal” range of free testosterone can vary based on the lab, and different guidelines may recognize different ranges of free testosterone.

A general rule of thumb is that free testosterone less than 50–65 picogram per milliliter (pg/mL) is considered low. However, this is often evaluated in the setting of low total testosterone (Trost, 2016).

What can cause low testosterone?

Some conditions that can lead to low testosterone levels include (Sizar, 2022):

Damage to testes

Chemotherapy or radiation

Autoimmune diseases

Infections

Thyroid dysfunction

Pituitary gland dysfunction

Medication side effects, especially narcotics and antidepressants

Treating the underlying conditions that cause low T may normalize your testosterone levels.

If your testosterone measurements are abnormal, your healthcare provider may want to run additional lab tests like luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) to learn more.

What happens if you have low free testosterone levels?

Even if your total testosterone concentration test results are average, you may still have low free testosterone levels. Low free testosterone levels may lead to frustrating symptoms of hypogonadism, including (Sizar, 2022):

Decreased sex drive (libido)

Erectile dysfunction, including loss of morning erections

Lean muscle mass loss

Body and facial hair loss

Fatigue (feeling tired all the time)

Weight gain or obesity

Depression

Anemia

Bone weakening (osteoporosis)

Can you have too much testosterone?

The answer is yes–both biological men and women can have too much testosterone.

The most common cause of too much testosterone (androgens) in men is the use of anabolic steroids, like the performance-enhancing steroids sometimes used by professional athletes. Other causes of high testosterone in men include testicular or adrenal gland tumors. High testosterone in men can cause the following (Ganesan, 2021):

Increased risk of prostate cancer

Male breast enlargement (gynecomastia)

Sleep apnea

Aggressive mood

Elevated blood pressure (hypertension)

High cholesterol (dyslipidemia)

Increased red blood cell count (erythrocytosis) and clotting problems

Shrinking testicles

In women, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of high testosterone levels. PCOS is due to an imbalance in the ratio of female to male hormones. Women with PCOS may experience irregular menstrual cycles, abnormal hair growth (hirsutism), infertility, acne, weight gain/obesity, and ovarian cysts (Rasquin Leon, 2022).

Declining testosterone levels are a normal part of aging. But, if you suspect low testosterone is causing frustrating symptoms, schedule an appointment with your healthcare provider. They will order blood tests to measure your free and total testosterone levels and create a treatment plan (if necessary) that’s right for you.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Antonio, L., Wu, F. C., O'Neill, T. W., et al. (2016). Low free testosterone is associated with hypogonadal signs and symptoms in men with normal total testosterone. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism , 101 (7), 2647–2657. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-4106. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26909800/

Ganesan, K., Rahman, S., & Zito, P. M. (2021). Anabolic steroids. StatPearls . Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482418/ .

Handelsman, D. J., Yeap, B., Flicker, L., et al. (2015). Age-specific population centiles for androgen status in men. European Journal of Endocrinology , 173 (6), 809–817. doi:10.1530/EJE-15-0380. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26385186/

Nassar, G. N. & Leslie, S. W. (2022) Physiology, testosterone. StatPearls. Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526128/

Rasquin Leon, L. I., Anastasopoulou, C., & Mayrin, J. V. (2022). Polycystic ovarian disease. StatPearls. Retrieved on Nov. 10, 2023 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459251/

Sizar, O. & Schwartz, J. (2022). Hypogonadism. StatPearls . Retrieved on Nov. 10, 2023 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532933/

Snyder, P. J. (2020). Approach to older men with low testosterone. In: Matsumoto, A. M., Schmader, K. E., & Martin, K. A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-older-men-with-low-testosterone

Trost, L. W. & Mulhall, J. P. (2016). Challenges in testosterone measurement, data interpretation, and methodological appraisal of interventional trials. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 13 (7), 1029–1046. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.04.068. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27209182/ .

Zarotsky, V., Huang, M., Carman, W., et al. (2014). Systematic literature review of the epidemiology of nongenetic forms of hypogonadism in adult males. Journal of Hormones , 2014, Article ID 19034. doi:10.1155/2014/190347. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jhor/2014/190347/