Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Have you ever heard that eating grapefruit might be good for your heart? That could be because of lycopene, a plant compound in many pink or red fruits, such as grapefruit. Lycopene isn’t just good for your heart, though. There’s also a link between lycopene and prostate health, along with other possible benefits.

What is lycopene?

Lycopene is a naturally occurring plant compound. It gives fruits such as tomatoes (and tomato products), pink grapefruit, watermelon, papaya, and guava their pink or red color. It is a member of the family of plant pigments called carotenoids. However, unlike other carotenoids (like beta-carotene and lutein), lycopene does not turn into vitamin A in the body (Imran, 2020).

Lycopene is a potent antioxidant that can help protect your cells from damage by eliminating free radicals. Free radicals are thought to damage cells which can potentially lead to diseases like cancer. Antioxidants like lycopene can help your body eliminate those radicals to reduce damage and promote healthy cells (Imran, 2020).

Given its antioxidant activity, studies are looking into lycopene’s potential ability to reduce the risk of cancer, especially prostate cancer (Imran, 2020).

Lycopene and prostate cancer

Several studies have looked at the potential health benefits of lycopene in decreasing the risk of prostate cancer. The results are mixed.

Some research in cell cultures (not in human beings) shows that lycopene can prevent the growth of prostate cancer cells by blocking critical cell communication pathways (Assar, 2016).

One study looking at a cohort of thousands of men showed that taking lycopene was linked to a lower risk of prostate cancer. This result was especially true if the men ate tomato sauce, a significant source of dietary lycopene, two or more times per week, compared to men who ate it less often (Giovannucci, 2002).

Another study looking at the same cohort of men showed that a high intake of lycopene, mainly from tomatoes, was linked to a lower risk of lethal prostate cancer (Zu, 2014).

Another study looked at the effects of lycopene on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH—also known as enlarged prostate). It found no solid evidence to say lycopene can prevent or treat BPH (Ilic, 2012).

The bottom line here: It is not definitive, but lycopene may decrease prostate cancer risk. More research in this area is needed (Chen, 2015).

Other health benefits of lycopene

Lycopene may have some positive impacts on other aspects of health.

Other cancers

Diets rich in lycopene are generally associated with a lower risk of certain cancers. Still, none of the studies says that lycopene directly prevents or treats cancer. In addition, it is not yet clear whether the lower risk is related to lycopene itself or other factors associated with lycopene-rich diets.

Some studies suggest that consuming lycopene and other carotenoids may reduce the risk of breast cancer (Story, 2010; Cui, 2008).

There have been inconsistent findings concerning lycopene and lung cancer. It may slightly lower your lung cancer risk, but it is also possible that people with a high intake of lycopene also have a diet that is rich in fruits and vegetables and an overall healthier lifestyle (Gallicchio, 2008).

Similarly, other studies are looking at how lycopene can affect the risk of colorectal, gastric, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Again, some show a benefit, and others show no change in cancer risk (Story, 2010).

Heart and blood vessels

Taking lycopene may also have a protective effect on the heart and blood vessels.

Several studies have shown that high levels of lycopene are associated with a lower risk of stroke and incidence of heart disease (cardiovascular disease). For example, one study found that men who eat lots of tomatoes and tomato-based products may have a 55% lower risk for stroke (Karppi, 2012).

This result may be because of lycopene’s potential ability to affect cholesterol levels. Some trials report that lycopene may lower LDL (“bad cholesterol) levels and increase HDL (“good” cholesterol) levels (Story, 2010).

Other studies show a potential benefit of lycopene in reducing blood pressure (Burton-Freeman, 2014). Still, the effect that lycopene intake may have on the risk of heart disease is unclear.

Good sources of lycopene

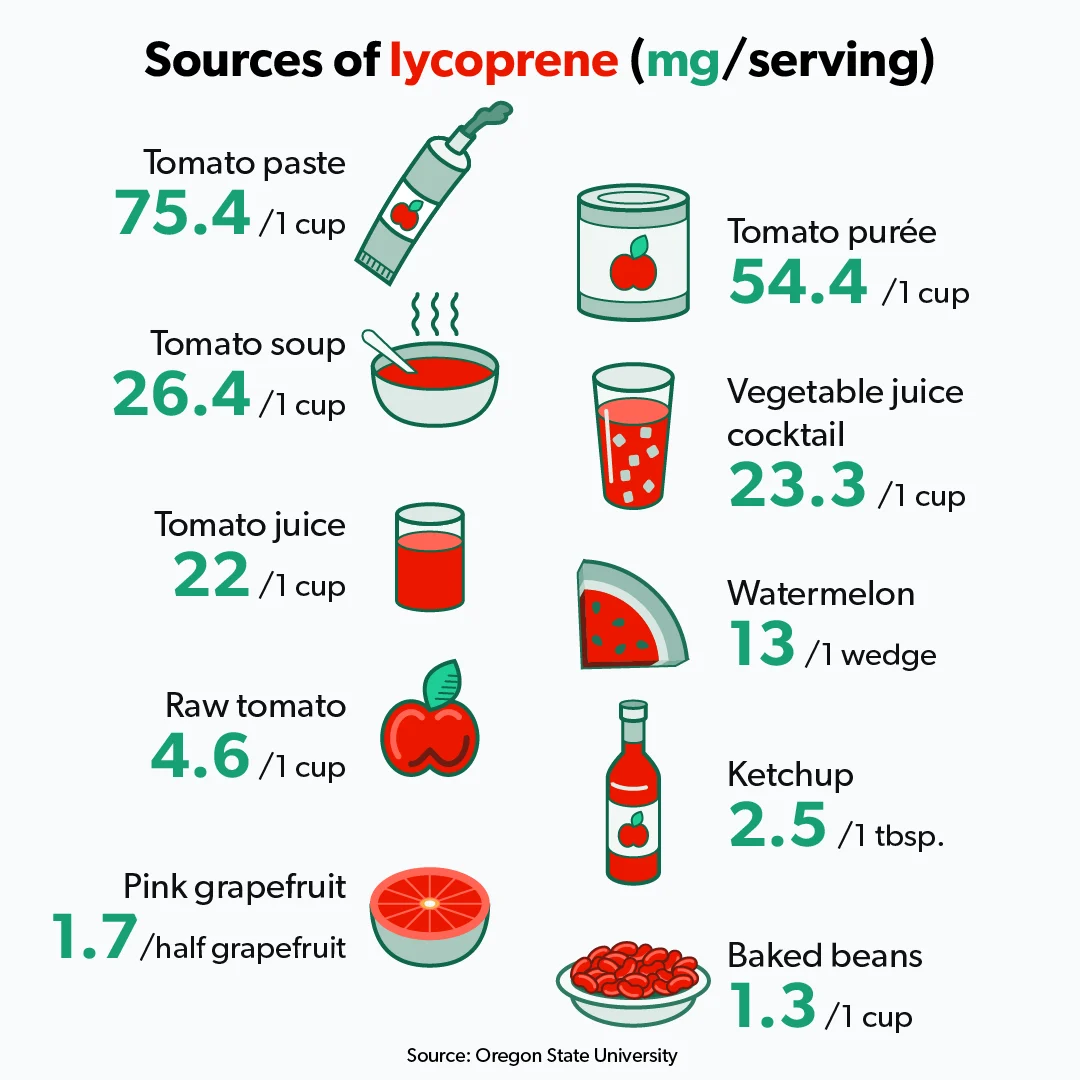

Lycopene is available from several food sources, especially red or pink-colored fruits like watermelon, pink grapefruit, and guava. However, over 85% of the lycopene consumed in the United States comes from tomatoes and tomato products (tomato sauce, tomato juice, tomato paste, ketchup, etc.) (Burton-Freeman, 2014). Interestingly, the lycopene content varies; the riper the tomato, the more lycopene it has (Carillo-Lopez, 2012).

There are no official recommendations regarding daily lycopene intake, but it is estimated that 35-75 mg of lycopene per day may be required before people with cancer would get the health benefits associated with lycopene’s antioxidant properties (USDA, n.d.).

Here’s a list of some common foods that may be good sources of lycopene. As you can see, some are better than others (Higdon, 2016):

Cooking and processing foods with lycopene, like tomatoes, actually makes lycopene more available and easier to absorb by your body; this is in contrast to other carotenoids, like beta-carotene, that break down with cooking. Also, being a fat-soluble compound, ingesting lycopene in oil-rich meals can improve absorption (Higdon, 2016).

If you do not think that you are not getting enough dietary lycopene, you can also take lycopene supplements; studies show that your ability to absorb lycopene from lycopene supplements is the same as for processed tomato products (Cohn, 2004). However, you may derive more health benefits from dietary lycopene because it’s often accompanied by other healthy micronutrients, like other carotenoids, vitamin C, etc.

Side effects of lycopene

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), lycopene is safe, and there have been no significant side effects reported.

No severe interactions between lycopene and other drugs have been reported. But if you take lycopene or any kind of dietary supplements, it’s always a good idea to let your healthcare provider know.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Assar, E. A., Vidalle, M. C., Chopra, M., & Hafizi, S. (2016). Lycopene acts through inhibition of IκB kinase to suppress NF-κB signaling in human prostate and breast cancer cells. Tumor Biology, 37(7), 9375–9385. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4798-3. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26779636/

Burton-Freeman, B. M., & Sesso, H. D. (2014). Whole food versus supplement: comparing the clinical evidence of tomato intake and lycopene supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors. Advances in Nutrition, 5(5), 457–485. doi: 10.3945/an.114.005231. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4188219/

Carrillo-López, A., & Yahia, E. M. (2012). Changes in color-related compounds in tomato fruit exocarp and mesocarp during ripening using HPLC-APcI -mass Spectrometry. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(10), 2720–2726. doi: 10.1007/s13197-012-0782-0. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25328217/

Chen, P., Zhang, W., Wang, X., Zhao, K., Negi, D. S., Zhuo, L., et al. (2015). Lycopene and Risk of Prostate Cancer. Medicine, 94(33). doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000001260. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26287411/

Cohn, W., Thürmann, P., Tenter, U., Aebischer, C., Schierle, J., & Schalch, W. (2004). Comparative multiple dose plasma kinetics of lycopene administered in tomato juice, tomato soup or lycopene tablets. European Journal of Nutrition, 43(5), 304–312. doi: 10.1007/s00394-004-0476-0. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15309451/

Cui, Y., Shikany, J. M., Liu, S., Shagufta, Y., & Rohan, T. E. (2008). Selected antioxidants and risk of hormone receptor-defined invasive breast cancers among postmenopausal women in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 87(4), 1009–1018. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1009. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18400726/

Gallicchio, L., Boyd, K., Matanoski, G., Tao, X.G., Chen, L., Lam, T. K.,et al. (2008). Carotenoids and the risk of developing lung cancer: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 88(2), 372–383. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.372. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18689373/

Giovannucci, E. (2002). A prospective study of tomato products, lycopene, and prostate cancer risk. CancerSpectrum Knowledge Environment, 94(5), 391–398. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.391. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11880478/

Higdon, Jane. (2016). α-Carotene, β-Carotene, β-Cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin. Oregon State University—Linus Pauling Institute. Retrieved Nov 17, 2019 from https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/dietary-factors/phytochemicals/carotenoids

Ilic, D., & Misso, M. (2012). Lycopene for the prevention and treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer: A systematic review. Maturitas, 72(4), 269–27. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.014. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22633187/

Imran, M., Ghorat, F., Ul-Haq, I., Ur-Rehman, H., Aslam, F., Heydari, M., et al. (2020). Lycopene as a natural antioxidant used to prevent human health disorders. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(8), 706. doi: 10.3390/antiox9080706. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7464847/

Karppi, J., Laukkanen, J. A., Sivenius, J., Ronkainen, K., & Kurl, S. (2012). Serum lycopene decreases the risk of stroke in men: a population-based follow-up study. Neurology, 79(15), 1540–1547. Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e26a6. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23045517/

MedlinePlus. (2019). Supplements: Lycopene. Retrieved Nov 17, 2019, from https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/natural/554.html#Safety6

Story, E. N., Kopec, R. E., Schwartz, S. J., & Harris, G. K. (2010). An update on the health effects of tomato lycopene. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 1(1), 189–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.102308.124120. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22129335/

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2012). Lycopene Handling. Retrieved from: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Lycopene%20TR.pdf

Zu, K., Mucci, L., Rosner, B. A., Clinton, S. K., Loda, M., Stampfer, M. J., & Giovannucci, E. (2014). Dietary lycopene, angiogenesis, and prostate cancer: a prospective study in the prostate-specific antigen era. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 106(2), djt430. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt430. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24463248/