BMI Calculator

BMI (body mass index) is one way to check if your weight is in a healthy range based on your height. It doesn’t show how much is muscle, bone, or fat, but it can help you understand your weight-related health risks. Use the tool below to calculate yours.

0.0

Your BMI

Underweight

< 18.5

Healthy weight

18.5 - 24.9

Overweight

24.9 - 29.9

Obesity

> 30

What is BMI?

Body mass index (BMI) is a widely used tool for estimating body fat based on your height and weight. While it doesn’t directly measure body fat, BMI can help start to identify whether you are underweight, within a healthy weight range, or living with overweight or obesity.

Healthcare providers frequently use BMI as a screening measure, not a diagnostic one. Meaning, a BMI score can suggest whether you may be at risk for certain health conditions, particularly those related to weight (e.g. type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease). It can also help providers determine whether you qualify for prescription weight loss treatments like Zepbound or Wegovy.

However, BMI doesn’t provide a full picture of your health. It doesn’t account for muscle mass, bone density, or fat distribution—all of which can influence health outcomes independently of BMI. Biological sex, age, and ethnicity are also not factored into BMI, despite being key predictors of body composition and disease risk.

That said, BMI can still be a helpful starting point. Large studies have found that BMI is strongly associated with the risk of developing conditions like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers, especially when considered alongside other markers like waist circumference and metabolic health indicators.

How to calculate BMI

BMI is calculated by dividing your weight in kilograms by your height in meters squared (kg/m²).

BMI = weight (kg) ÷ height² (m²)

BMI = [weight (lb) ÷ height² (in²)] × 703

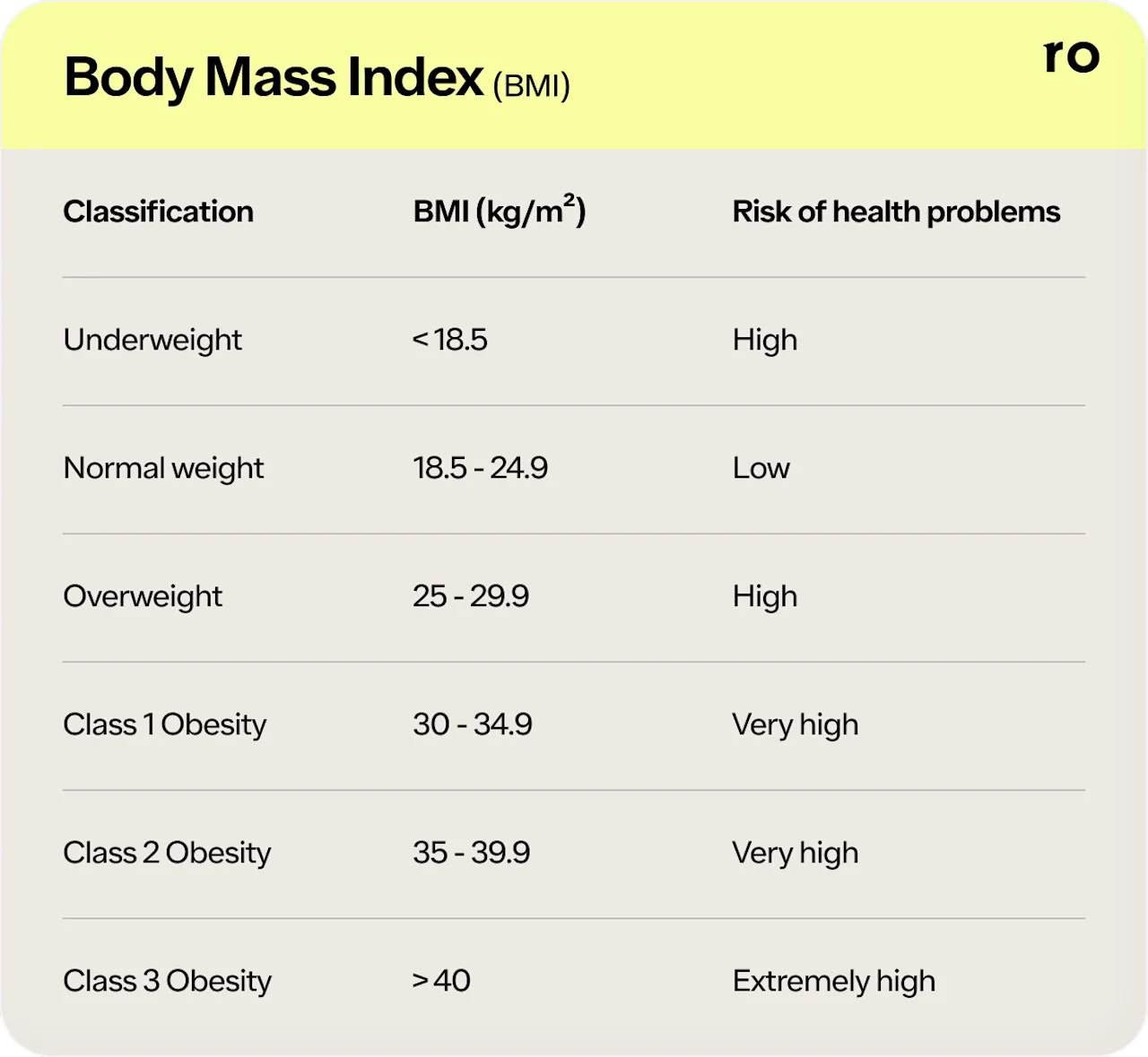

BMI measurements are typically divided into four main categories: underweight, normal, overweight, and obesity. Obesity is further broken down into three classes. These classifications are based on BMI ranges defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and they apply to adults aged 20 and older:

Underweight: <18.5

Normal: 18.5–24.9

Overweight: 25–29.9

Class 1 Obesity: 30–34.9

Class 2 Obesity: 35–39.9

Class 3 Obesity: >40

These categories do not apply to children, teens, or pregnant individuals. They also may not tell the full story or accurately reflect health risk for all adults.

BMI doesn’t distinguish between muscle and fat, nor does it account for fat distribution, particularly visceral fat, which is more strongly associated with cardiometabolic risk. For this reason, many healthcare providers also look at other metrics, such as waist circumference, lifestyle factors, and metabolic labs, when assessing weight and overall health.

What does my BMI number mean?

Once you calculate your BMI, it will fall into one of the standard categories: underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obesity. These categories offer a general sense of how your weight may relate to your risk for certain health conditions.

Underweight (<18.5): Being underweight can be associated with increased risks of malnutrition, weakened immune function, osteoporosis, and early death, especially among older adults and hospitalized populations.

Normal weight (18.5–24.9): This range is generally considered to carry the lowest overall risk of chronic diseases.

Overweight (25–29.9): Individuals in this category may be at an elevated risk for high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and heart disease, especially when paired with other risk factors like excess abdominal fat.

Class 1 Obesity (30–34.9): This level of obesity can be associated with significantly increased risks for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (e.g. high blood pressure), and sleep apnea.

Class 2 Obesity (35–39.9): The second level of obesity can come with a greater risk for cardiometabolic diseases and is often associated with reduced mobility and liver disease.

Class 3 Obesity (>40): People in this category tend to face the highest risk for serious chronic conditions, including those mentioned above as well as certain cancers.

Keep in mind that BMI is just one piece of the puzzle. While it may flag potential health risks, it doesn’t explain why someone may fall into a given category or what could be happening beneath the surface. That’s where a closer look at other health indicators becomes important.

What does my BMI measurement not tell me?

We’ve mentioned it before, but it’s worth emphasizing: BMI may have its uses, but it doesn’t account for everything that matters when it comes to your health.

So, what isn’t your BMI telling you?

How much of your weight is muscle vs. fat. BMI doesn’t distinguish between lean mass and body fat. That means someone with a high level of muscle mass—think: an athlete—may be classified as having overweight or obesity, even if their body fat is low and other health markers are considered optimal.

Where fat is stored in your body. Research has shown that fat concentrated in the abdominal area (visceral fat) can pose a greater health risk than fat distributed elsewhere. Yet two people with the same BMI might have very different body compositions and levels of risk depending on how their fat is distributed.

Your metabolic health. BMI doesn’t evaluate or provide information about blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, or inflammation levels.

Your fitness level or physical strength. You could be as active and physically fit as an Olympian, but your BMI won’t reflect it. Studies show that people with higher BMIs who are physically fit may be healthier—and live longer—than those with lower BMIs who don’t exercise regularly.

Your biological age, sex, or genetics. All of these factors can influence your body composition and how it can affect your overall health, yet they’re not included in your BMI measurement. Biological women, for example, have greater amounts of total body fat than men with equal BMIs.

Your race and ethnicity. The BMI system was created based on studies conducted on almost exclusively white populations, and the majority of data that backs the calculation is from, yup, white populations. However, different races and ethnicities gain weight and respond to weight gain differently. For example, research suggests that Asian Americans tend to develop obesity-related comorbidities (i.e. health issues) at lower BMIs than white Americans. This is just one of the reasons why some experts have suggested adjusting BMI categories for ethnicities.

Your habits and lifestyle. Similar to your physical fitness, BMI doesn’t account for other behaviors like how (and what) you eat, sleep, or manage stress—all of which can impact your weight and, in turn, your BMI.

How to use your BMI range

Think of your BMI range as a starting point—not a verdict. On its own, BMI can’t tell you everything about your health, but it can offer a useful frame of reference for deeper conversations with your healthcare provider.

If your BMI falls in the normal range, it suggests that your weight is less likely to be associated with certain chronic conditions. But it’s still important to pay attention to other markers like blood pressure, cholesterol, energy levels, and overall wellbeing.

If your BMI is in the underweight, overweight, or obesity range, that doesn’t automatically mean you’re unhealthy or need to make drastic changes. But it may be a sign to take a closer look at your lifestyle, eating habits, physical activity, and other health metrics. In some cases, a higher BMI may make you eligible for medical support like prescription weight loss medications (i.e. pills or injections) or clinical care programs.

No matter your number, the most helpful next step is to speak with a healthcare provider who can evaluate the full picture—your goals, lab work, family and personal medical history, mental health, and more—and help you decide what makes sense for you and your body.

References

Barry, V. W., Baruth, M., Beets, M. W., Durstine, J. L., Liu, J., & Blair, S. N. (2014). Fitness vs. fatness on all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 56(4), 382–390. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.002. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0033062013001552

Bhaskaran, K., Douglas, I., Forbes, H., dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D. A., & Smeeth, L. (2014). Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. Lancet (London, England), 384(9945), 755–765. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60892-8/fulltext

Després J. P. (2012). Body fat distribution and risk of cardiovascular disease: an update. Circulation, 126(10), 1301–1313. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067264. Retrieved from https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.067264

Flegal, K. M., Kit, B. K., Orpana, H., & Graubard, B. I. (2013). Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 309(1), 71–82. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.113905. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1555137

Guh, D. P., Zhang, W., Bansback, N., Amarsi, Z., Birmingham, C. L., & Anis, A. H. (2009). The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 9, 88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. Retrieved from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

Jensen, M. D., Ryan, D. H., Apovian, C. M., Ard, J. D., Comuzzie, A. G., Donato, K. A., Hu, F. B., Hubbard, V. S., Jakicic, J. M., Kushner, R. F., Loria, C. M., Millen, B. E., Nonas, C. A., Pi-Sunyer, F. X., Stevens, J., Stevens, V. J., Wadden, T. A., Wolfe, B. M., Yanovski, S. Z., Jordan, H. S., … Obesity Society (2014). 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation, 129(25 Suppl 2), S102–S138. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109713060300

Li, Z., Daniel, S., Fujioka, K., & Umashanker, D. (2023). Obesity among Asian American people in the United States: A review. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 31(2), 316–328. doi:10.1002/oby.23639. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10108164/

Neeland, I. J., Ross, R., Després, J. P., Matsuzawa, Y., Yamashita, S., Shai, I., Seidell, J., Magni, P., Santos, R. D., Arsenault, B., Cuevas, A., Hu, F. B., Griffin, B., Zambon, A., Barter, P., Fruchart, J. C., Eckel, R. H., International Atherosclerosis Society, & International Chair on Cardiometabolic Risk Working Group on Visceral Obesity (2019). Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology, 7(9), 715–725. doi10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30084-1. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landia/article/PIIS2213-8587(19)30084-1/abstract

Nuttall F. Q. (2015). Body Mass Index: Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review. Nutrition Today, 50(3), 117–128.doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000092. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4890841/

Pi-Sunyer, F. X. (2009). The medical risks of obesity. Postgraduate Medicine, 121(6), 21–33. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2074. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2074

Prospective Studies Collaboration, Whitlock, G., Lewington, S., Sherliker, P., Clarke, R., Emberson, J., Halsey, J., Qizilbash, N., Collins, R., & Peto, R. (2009). Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet (London, England), 373(9669), 1083–1096. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(09)60318-4/fulltext

Walter, S., Mejía-Guevara, I., Estrada, K., Liu, S. Y., & Glymour, M. M. (2016). Association of a Genetic Risk Score With Body Mass Index Across Different Birth Cohorts. JAMA, 316(1), 63–69. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8729. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2532014

Meet our expert

When it comes to weight loss, biology is your nemesis. Not willpower. Our very own Dr. Steve explains why.

Thousands of members and counting

Real members, real weight loss results

Don't just take it from us—our members see (and feel) the difference. These members were paid in exchange for their testimonials.

87% have seen life-changing results*

93% agree Ro is easier to incorporate into their lives*

97% report silenced or quieter food noise since starting*

Average weight loss in 1 year is 14-20% (vs 2.2-3.1% with diet and exercise alone). Based on studies of branded medications in non-diabetics with obesity, or with overweight plus a weight-related condition, with diet and exercise.

*Based on survey results of 1,243 Ro members taking GLP-1 medication for at least 7 weeks, paired with diet and exercise.

A full suite of GLP-1 weight loss medications

Ozempic is FDA-approved for type 2 diabetes treatment, but may be prescribed off-label for weight loss at a healthcare provider’s discretion.