Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Obesity rates have been on the rise for decades. Some researchers view it as one of the biggest health concerns worldwide because of the other conditions associated with it.

But obesity is complex, and addressing it goes far beyond the standard advice of “eating less and exercising more.” Let’s dig into the many possible causes of obesity to understand this multifaceted condition.

What is obesity?

Obesity is a complex health issue associated with an increased risk of numerous chronic health problems, including high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and more.

Many factors make it more challenging for some people to maintain a healthy weight than others. The development of obesity can result from genetics, environment, stress, and other physiological factors (Panuganti, 2021).

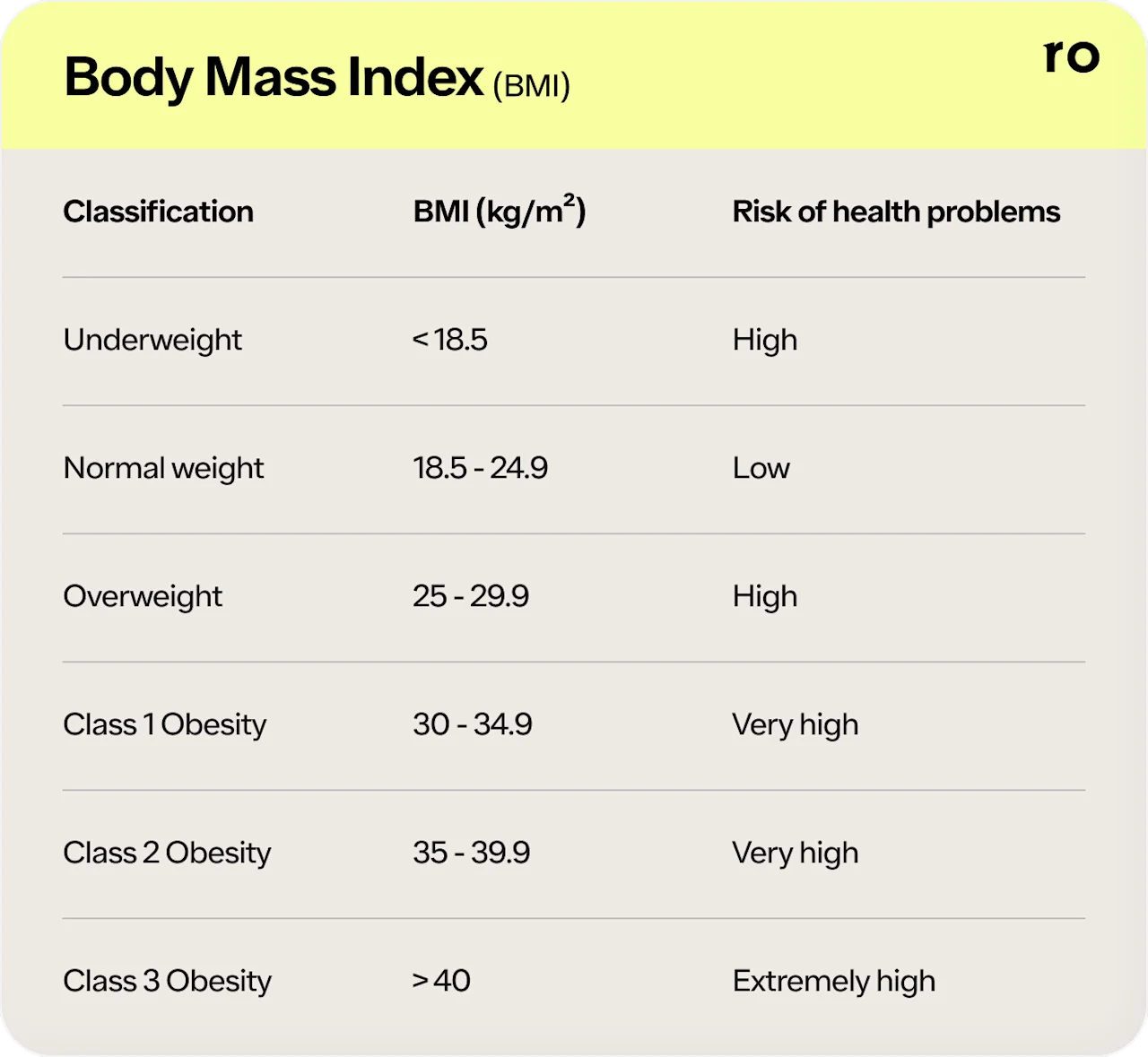

Overweight and obesity are classified using body mass index (BMI).

What is BMI?

BMI is a measure that compares the ratio of weight to height. Here are the categories of BMI (Nuttall, 2015):

While BMI is a helpful tool for researchers to assess populations, it doesn’t tell the whole story. This measurement tool solely compares weight to height. A BMI assessment alone doesn’t tell you how much of your body weight is fat, muscle, bone, and other lean tissues.

So, while BMI can be a decent reference, it’s not very accurate because of many outliers. For example, athletes and muscular people will have a higher BMI but may still land in the obesity category despite having lower body fat.

10 causes of obesity

Many factors can influence your weight. Here are some of the potential causes of obesity:

1. Genetics

Your family history strongly influences the development of obesity. Children whose parents have obesity are more likely to develop it than others whose parents have a lower BMI (Panuganti, 2021).

However, even if genetics puts you at a higher risk for gaining weight, that doesn’t mean you’ll develop obesity. Environmental factors also play a big role in how genes are expressed. For example, the food you eat and your activity level can influence whether a gene turns on.

2. Hormonal imbalances

The human body has systems that naturally regulate and maintain body weight. Our hormones play a big role in this process.

Here are some of the hormones that influence appetite and weight:

Insulin: This hormone is best known for its role in diabetes. Insulin is responsible for signaling cells to bring in glucose (blood sugar) from the bloodstream. The exact role insulin plays in obesity is unclear. Still, research demonstrates a relationship between obesity, insulin resistance, and the risk of type 2 diabetes (Mead, 2017).

Glucagon: This hormone does the opposite of insulin. When blood sugar starts to dip too low, or the body perceives it needs more energy, it releases glucagon to bring energy out of storage and raise blood sugar levels. A 2021 study found that higher glucagon levels were associated with having a larger waist circumference. Lower fasting glucagon was associated with a lower risk for diabetes (Hamasaki, 2021).

Leptin: This hormone is primarily produced by fat cells and reduces appetite, food intake, and in turn, body weight. However, some people can develop a resistance to leptin, which decreases the effectiveness of this weight regulation hormone (Panuganti, 2021).

Ghrelin: This hormone stimulates appetite and drives you to eat. It also plays a role in glucose and energy balance by reducing insulin secretion. Researchers and drug companies have started targeting medications that reduce the effects of ghrelin in an attempt to curb appetite and reduce energy intake (Pradhan, 2013). One study found frequent weight loss attempts followed by weight regain (often called yo-yo dieting) were associated with high ghrelin levels (Hooper, 2010).

Cortisol: Also known as the stress hormone, cortisol influences many things in the body. Researchers suggest high cortisol levels play a role in the development of obesity (van der Valk, 2018).

3. Diet high in processed foods and sugar

A diet high in sugar is strongly associated with weight gain and obesity. Research indicates most people in the US consume more than 300% of the recommended daily limit for added sugar (Faruque, 2019).

In addition, the way food is processed can influence your taste preferences.

For example, when creating a strawberry-flavored product, companies tend to take one portion of the flavor profile. So, instead of tasting the variety of flavors of a strawberry, you taste an intensified and concentrated flavor. Your taste buds can become accustomed to the intensity of that flavor and may have trouble noticing the flavors of the whole food. This can create a vicious cycle, where you’re less likely to choose whole foods over processed foods. While that’s totally fine in moderation, if your diet is primarily made up of ultra-processed foods, it will be less nutritious overall (Svisco, 2019).

4. Chronic stress

Over time, high stress levels can take a toll on the body and hormone balance. Here are a few ways stress can influence the development of obesity (van der Valk, 2018):

Research suggests increased cortisol levels caused by stress may redistribute fat into the stomach area and increase food cravings.

Epinephrine, also known as adrenaline, triggers the flight-or-fight response. It prepares you to take action when in danger. For example, when your ancestors were walking through the woods and came across a bear, adrenaline provided them with an increase in energy and blood flow to help them run away or defend themselves. But we still have this response to modern-day stressors, leaving us with increased heart rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar level while sitting at a work desk.

During the stress response, glucagon is released to help bring glucose out of cells, so it’s easily available for energy.

5. Emotional eating

Another potential cause of obesity is emotional eating is because it can lead to eating beyond feeling full. Eating—along with buying things, drinking alcohol, taking drugs, watching tv, reading, getting hugs, exercising, and many other actions—can trigger the release of dopamine and pleasure.

So all of these actions can be used to cope with emotions, but some can be more harmful to your health than others.

People who frequently use food to cope with emotions often eat more food than their body needs and consistently ignore their body’s fullness cues, which may lead to hormonal and physiological changes (Konttinen, 2020).

6. Medication

Certain medications may lead to weight gain as a side effect. Here are some examples of drugs that may cause weight gain (Domecq, 2015):

Antidepressants such as amitriptyline and mirtazapine (Remeron)

Steroids, like prednisone

Antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, quetiapine (Seroquel), and risperidone

Anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers, such as gabapentin and divalproex

Diabetes medication, such as tolbutamide, pioglitazone, glimepiride, gliclazide, glyburide, glipizide, sitagliptin, and nateglinide

7. Food availability

It’s much easier to get food now than centuries ago when people needed to hunt and gather, and had less reliable food storage. The ability to preserve foods and keep foods frozen helps increase access to food.

Before, meats, for example, could be salted or allowed to dry out (like vegetables or herbs), helping them last longer. Now, refrigeration and freezers extend the freshness of food. In addition, restaurants and fast food are available everywhere, so it’s much easier now to consistently eat more food than you need.

Still, it can be tricky to get more nutritious foods in some areas, especially low-income areas.

Food deserts are areas with limited access to affordable and nutritious foods. In these areas, there are few grocery stores. Instead, most food is highly processed and purchased from gas stations or convenience stores. Obesity rates tend to be higher in these areas.

8. Sedentary lifestyle

The modern lifestyle is more convenient and usually requires significantly less activity than previous generations got in a day. Automatic vacuums, riding lawn mowers, cars, and desk jobs all decrease the need to move throughout the day.

So, people naturally move significantly less throughout the day because less manual labor is required to accomplish daily tasks.

Even if people spend 30–45 minutes working out daily, it’s only a small portion of the day. The rest of the day, most people tend to go from lying in bed at night, to riding in a car for their commute, to sitting at a desk all day, to sitting on the couch to unwind in the evenings before going to bed.

9. Conflicting and confusing information

It can be challenging for the average person to know what information to trust. There seems to be a bottomless well of research and media articles discussing the best way to approach weight and health.

Media trends and fad diets have consistently gone back and forth on whether low-carb or low-fat is best. And multiple new diets seem to come out every year. If you’re having trouble finding an eating plan that works best for you, talk with your healthcare provider or a registered dietitian for information.

10. Frequent dieting attempts and weight cycling

Along with climbing obesity rates, the number of people participating in dieting and intentional weight loss has also increased.

Research shows that between 1950–1966, around 14% of women and 25% of men attempted to lose weight. Contrast that with 57% of women and 40% of men reporting attempted weight loss between 2003–2008, and you can see how much this trend has exploded (Rhee, 2017).

Weight cycling, also known as yo-yo dieting, is defined as repeated weight loss attempts that result in weight loss followed by weight regain.

Studies have found a relationship between weight cycling and an increased risk for heart disease, renal diseases, and diabetes, though researchers are still trying to figure out why this would be.

Here is what the research says about the relationship between intentional weight loss attempts, weight cycling, and health (Dulloo, 2015; Rhee, 2017):

1–2 out of three people who intentionally lose weight will regain the weight within one year, and almost all will by the end of 5 years.

At least one-third of dieters regain more weight than they lost.

Dieting during childhood predicts future weight gain and increases the risk of obesity.

Dieting and weight cycling increase the risk of eating disorders and mental health conditions like anxiety and depression.

Weight cycling leads to fluctuations in blood pressure, heart rate, kidney function, glucose, lipids, and insulin levels. All these fluctuations may increase the risk for heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and liver diseases.

Since both weight loss attempts and obesity are prominent parts of modern culture, it can be difficult for researchers to determine causal relationships between these factors and health. More research is needed to understand the impacts of dieting, obesity, and how to protect long-term health.

Prevalence of obesity

The prevalence of obesity has been rising over the decades. From 1999 to 2018, obesity rates have risen from 30.5% to 42.4% of the US population.

Childhood obesity rates are also rising. Research suggests about 19.3% of children and adolescents have obesity (CDC, 2021).

Risk factors for obesity

Potential risk factors for developing obesity and excess weight include:

Family history

Unhealthy diet and regularly overeating

Lack of physical activity and sedentary lifestyle

Low socioeconomic status

Age

Medications and medical problems

Pregnancy

Stress

Lack of sleep

Smoking and smoking cessation

Complications of obesity

People who have obesity have an increased risk for developing other health problems, such as (Panuganti, 2021):

Diabetes

Heart disease (cardiovascular disease)

High blood pressure (hypertension)

High cholesterol levels

Cancer

Digestive problems

Sleep apnea

Osteoarthritis

Treatments for obesity

If you have obesity, there are options to support your health. You may be able to lose weight on your own, but don’t hesitate to reach out to your healthcare provider. They can support you in reaching a healthy weight and refer you to mental health professionals or dietitians as needed.

Here are some options to help manage obesity:

Lifestyle changes

Lifestyle interventions are usually the first step to managing weight. These include:

Moving more throughout the day

Exercising regularly

Eating a balanced, nutritious diet

Eating mindfully

Getting enough sleep

Staying hydrated by drinking water

Joining support groups

Meeting with a medical or health professional

Medical interventions

If you’re unable to manage obesity through lifestyle changes, your healthcare provider may explore medical options such as (Panuganti, 2021):

Medications: A few examples of FDA-approved medications to help treat obesity include orlistat, phentermine, and lorcaserin.

Weight loss surgery: People with severe obesity may be candidates for bariatric surgery like gastric banding or sleeve gastrectomy.

Be sure to discuss all the potential risks, complications, and benefits of medical options with your healthcare provider.

Find out how much you could lose

Provide your biometric data to get started.

0.0

Your BMI

Underweight

< 18.5

Healthy weight

18.5 - 24.9

Overweight

24.9 - 29.9

Obesity

> 30

When to see a healthcare provider

If you’re gaining weight and concerned about developing obesity, talk with your healthcare provider. Making changes early can help prevent medical complications and lower your risk for developing other chronic diseases.

Don’t hesitate to reach out for support if you have concerns about obesity and your health.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Adult obesity facts. Retrieved on Jan. 26, 2022 from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

Domecq, J. P., Prutsky, G., Leppin, A., et al. (2015). Clinical review: Drugs commonly associated with weight change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal Of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism , 100 (2), 363–370. doi:10.1210/jc.2014-3421. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5393509/

Dulloo, A. G. & Montani, J. P. (2015). Pathways from dieting to weight regain, to obesity and to the metabolic syndrome: an overview. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity , 16(1) , 1–6. doi:10.1111/obr.12250. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25614198/

Faruque, S., Tong, J., Lacmanovic, V., et al. (2019). The dose makes the poison: sugar and obesity in the united states - a review. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences , 69 (3), 219–233. doi:10.31883/pjfns/110735. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6959843/

Faruque, S., Tong, J., Lacmanovic, V., et al. (2019). The dose makes the poison: sugar and obesity in the united states - a review. Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences , 69 (3), 219–233. doi:10.31883/pjfns/110735. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6959843/

Hamasaki, H. & Morimitsu, S. (2021). Association of glucagon with obesity, glycemic control and renal function in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Canadian Journal of Diabetes , 45 (3), 249–254. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2020.08.108. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33129755/

Hooper, L. E., Foster-Schubert, K. E., Weigle, D. S., et al. (2010). Frequent intentional weight loss is associated with higher ghrelin and lower glucose and androgen levels in postmenopausal women. Nutrition Research , 30 (3), 163–170. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2010.02.002. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2992868/

Konttinen, H. (2020). Emotional eating and obesity in adults: the role of depression, sleep and genes. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society , 79 (3), 283–289. doi:10.1017/S0029665120000166. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32213213/

Panuganti, K. K., Nguyen, M., & Kshirsagar, R. K. (2021). Obesity. [Updated Aug 11, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Jan. 26, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459357/

Pradhan, G., Samson, S. L., & Sun, Y. (2013). Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care , 16 (6), 619–624. doi:10.1097/MCO.0b013e328365b9be. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24100676/

Mead, E., Brown, T., Rees, K., et al. (2017). Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 6 (6), CD012651. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012651. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6481885/

Nuttall, F. Q. (2015). Body mass index: obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutrition Today , 50 (3), 117–128. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000092. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4890841/

Rhee, E. J. (2017). Weight cycling and its cardiometabolic impact. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome , 26 (4), 237–242. doi:10.7570/jomes.2017.26.4.237. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489475/

Svisco, E., Byker Shanks, C., Ahmed, S., & Bark, K. (2019). Variation of adolescent snack food choices and preferences along a continuum of processing levels: the case of apples. Foods , 8 (2), 50. doi:10.3390/foods8020050. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6406983/

van der Valk, E. S., Savas, M., & van Rossum, E. (2018). Stress and obesity: are there more susceptible individuals?. Current Obesity Reports , 7 (2), 193–203. doi:10.1007/s13679-018-0306-y. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5958156/