Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Reading about chlamydia may transport you back to your school days—you and 20 of your peers sitting in a classroom for an hour every week to learn about sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Early education about STIs is key to helping prevent their spread.

Unfortunately, people may be nervous about talking about STIs with their healthcare providers. This is especially concerning for a condition like chlamydia, which can often be asymptomatic and can lead to problems if not recognized and treated appropriately.

What is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is an STI caused by the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. It was discovered in 1907 by Ludwig Halberstädter and Stanislaus von Prowazek while they were investigating people with trachoma. This disease causes inflammation of the inner eyelid (Taylor-Robinson, 2017).

Very generally, the term “chlamydia” may refer to a group of bacteria in the genus Chlamydia. One of the characteristics of these bacteria is that they are obligate intracellular organisms, meaning they have to live inside the cells of the host they are infecting to reproduce.

When Halberstädter and von Prowazek first discovered the bacteria and saw that it lived inside human cells, they named it Chlamydozoa from the Greek chlamys, meaning cloak. They also initially thought they had discovered a virus or protozoan (a single-celled organism). However, further testing confirmed that Chlamydia was a genus of bacteria that contained nine different species.

Chlamydia trachomatis, the species that causes the STI, is further divided into subtypes called serovars. The exact number of serovars differs from source to source, but they are generally divided into (Mohseni, 2021):

Serovars A–C: Cause trachoma (inflammation of the inner eyelid)

Serovars D–K: Cause infection of the internal and external genitalia, non-gonococcal urethritis (inflammation of the urethra that is not due to gonorrhea), proctitis (inflammation of the lining of the rectum), and conjunctivitis (a.k.a. pinkeye)

Serovars L1, L2, L3: Cause lymphogranuloma venereum or LGV (infection of the lymphatic system) and proctitis in men who have sex with men (MSM)

How prevalent is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is the most common reportable bacterial infection in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that there were approximately four million cases of chlamydia in the U.S. in 2018 (CDC, 2021).

That's more than double the number of cases of gonorrhea reported in the same year! Since most chlamydial infections are asymptomatic, the actual number of people infected with chlamydia is likely much higher than this. Rates of chlamydia are also increasing worldwide (Hsu, 2019-a).

An example of the rising rate can be seen with LGV, one of the diseases caused by certain types of chlamydia. Typically, LGV was found in tropical and subtropical regions globally, including Africa, the Caribbean, India, and Southeast Asia, and could infect heterosexuals. However, since 2003, outbreaks have been seen in North America and Western Europe. These outbreaks are primarily amongst MSM, most of whom also have HIV (de Vries, 2019).

What are the risk factors for getting chlamydia?

The risk factors for getting chlamydia include age, sex, race, and sexual activity (Hsu, 2019-a).

Age—The prevalence of chlamydia is highest in people aged 14–24. One study shows that the overall rate of infection in those aged 18–26 is 4.2%.

Sex—Females are approximately twice as likely to be infected as males. Around one in 20 sexually active females aged 14–24 are infected with chlamydia. Having a condition known as cervical ectopy, which is when cells from the inside of the cervix are present on the outside of the cervix, can make infection with chlamydia more likely (Torrone, 2014).

Race—The incidence of infection in African Americans is six times the incidence in whites, while the rate in Alaska Natives and Native Americans is 3.8 times the incidence in whites. Combining both race and sex, the prevalence of chlamydial infection in African American women is 14%.

Sexual activity—Chlamydia is spread through sexual activity. Being sexually active, having multiple partners, and not using barrier protection (such as condoms) are all risk factors for acquiring the infection. MSM are also at increased risk of being infected with chlamydia.

How is chlamydia passed from one person to another?

Chlamydia is transmitted through sexual contact, meaning that coming into contact with the anus, mouth, penis, or vagina of somebody infected may cause you to become infected. Anal, oral, and vaginal sex can all spread the infection even if ejaculation does not occur. However, you can't get chlamydia through kissing or sharing cups with somebody who has chlamydia.

Chlamydia can also spread from mother to child during birth around 50–70% of the time, causing pneumonia or conjunctivitis in the newborn (Hammerschlag, 2018).

What are the signs and symptoms of chlamydia?

One of the reasons chlamydia is so prevalent is that it is asymptomatic in most cases. People may not know they have chlamydia, so they do not seek treatment and may continue to spread it. It's estimated that only 10% of men and 5–30% of women experience symptoms. When infection with chlamydia does cause symptoms or complications, it is known as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) (CDC, 2021).

Chlamydia has different symptoms depending on the body part infected.

Universal chlamydial infections

Anyone can have the following infections (Hsu, 2019-b):

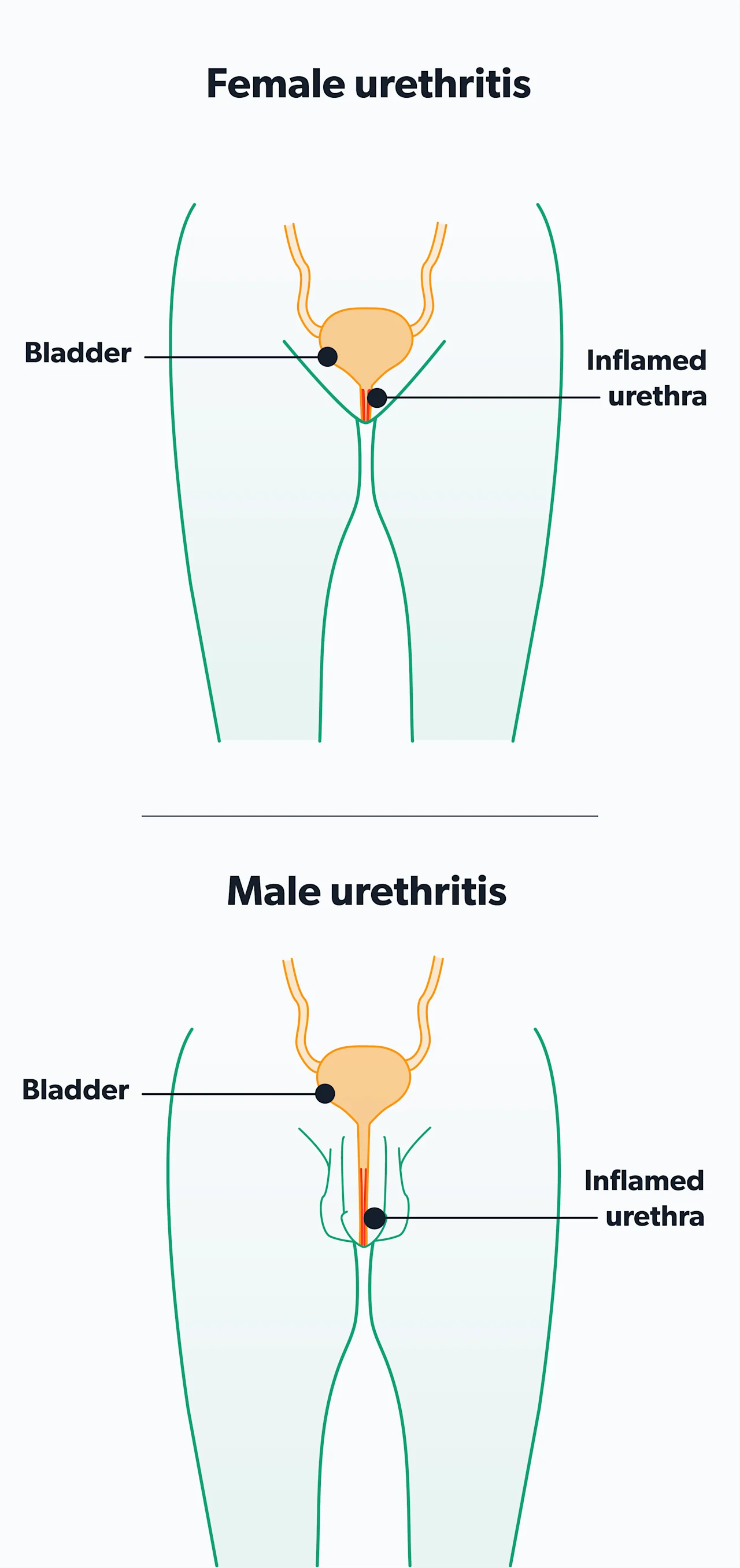

Infection of the urethra (urethritis)can lead to increased frequency of urination and pain or burning with urination (dysuria). In those with a penis, urethritis can lead to penile discharge and an itchy feeling at the opening of the penis. The discharge is typically watery and begins 5–10 days after exposure. It is low in volume, so it may only be noticeable when milking the penis or when stains show up on your underwear. This contrasts with the discharge seen with a gonorrheal infection, which is typically thicker and greater in volume.

Infection of the lymphatic system (LGV)—This infection can start with a non-painful genital ulcer and lead to swelling and pain of the lymph nodes in the groin.

Infection of the lining of the rectum (proctitis)—Proctitis in females is typically asymptomatic. The LGV serovars of chlamydia generally cause proctitis in MSM. It leads to rectal pain, discharge, bleeding, constipation, and the sensation of always needing to go to the bathroom (tenesmus).

Infection of the throat (pharyngitis)—Although not a common cause of sore throat, chlamydia can infect the throat.

Infection of the outer layer, or conjunctiva, of the eyes (conjunctivitis)—This infection may cause redness, tearing, and irritation of the infected eye.

Chlamydia in men

Infections and symptoms specific to biological males include (Hsu, 2019-b):

Infection behind the testes (epididymitis)—The epididymis is a coil of tubes attached to the back of the testicle. Infection of this area can lead to one- or two-sided scrotal swelling and pain.

Infection of the prostate (prostatitis)—Chlamydia may be a cause of chronic prostatitis (long-term inflammation of the prostate). This causes pain with urination, pain with ejaculation, pelvic pain, incontinence, and difficulty urinating.

Chlamydia in women

Infections and symptoms specific to biological females include (Hsu, 2019-b):

Infection of the cervix (cervicitis)—This infection rarely presents with symptoms, but when symptoms do occur, they are nonspecific. Symptoms may include vaginal discharge, bleeding between menstrual periods, and bleeding after sexual activity. These symptoms typically begin 7–14 days after exposure.

Ascending infection—If untreated, chlamydia can spread from the cervix to the rest of the reproductive system, even affecting other organs in the abdomen. This can cause pelvic and abdominal pain and is one of the complications of untreated chlamydia.

What are the complications of untreated chlamydia?

Chlamydia can be easily treated with antibiotics. However, because it is often asymptomatic, many people may go without treatment. Some may also go without treatment even if they have symptoms because of a lack of access to healthcare or because of perceived stigma surrounding their condition. Luckily, many cities have free clinics or reduced-cost clinics where the amount you pay depends on your income. These locations offer a judgment-free way for many people to easily receive treatment.

Some people still may not receive treatment, which can lead to complications as the infection spreads. In everybody, untreated chlamydial infection increases the risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Pillay, 2021).

Approximately 1% of biological males who have urethritis go on to develop a type of arthritis called reactive arthritis. This causes pain and swelling in the joints, typically affecting the knees and the feet (but it could be anywhere). In some cases, urethritis and reactive arthritis also occur with conjunctivitis or uveitis, which is inflammation of part of the eye that can cause blurred vision—this triad of symptoms is called Reiter’s syndrome (Hsu, 2019-b).

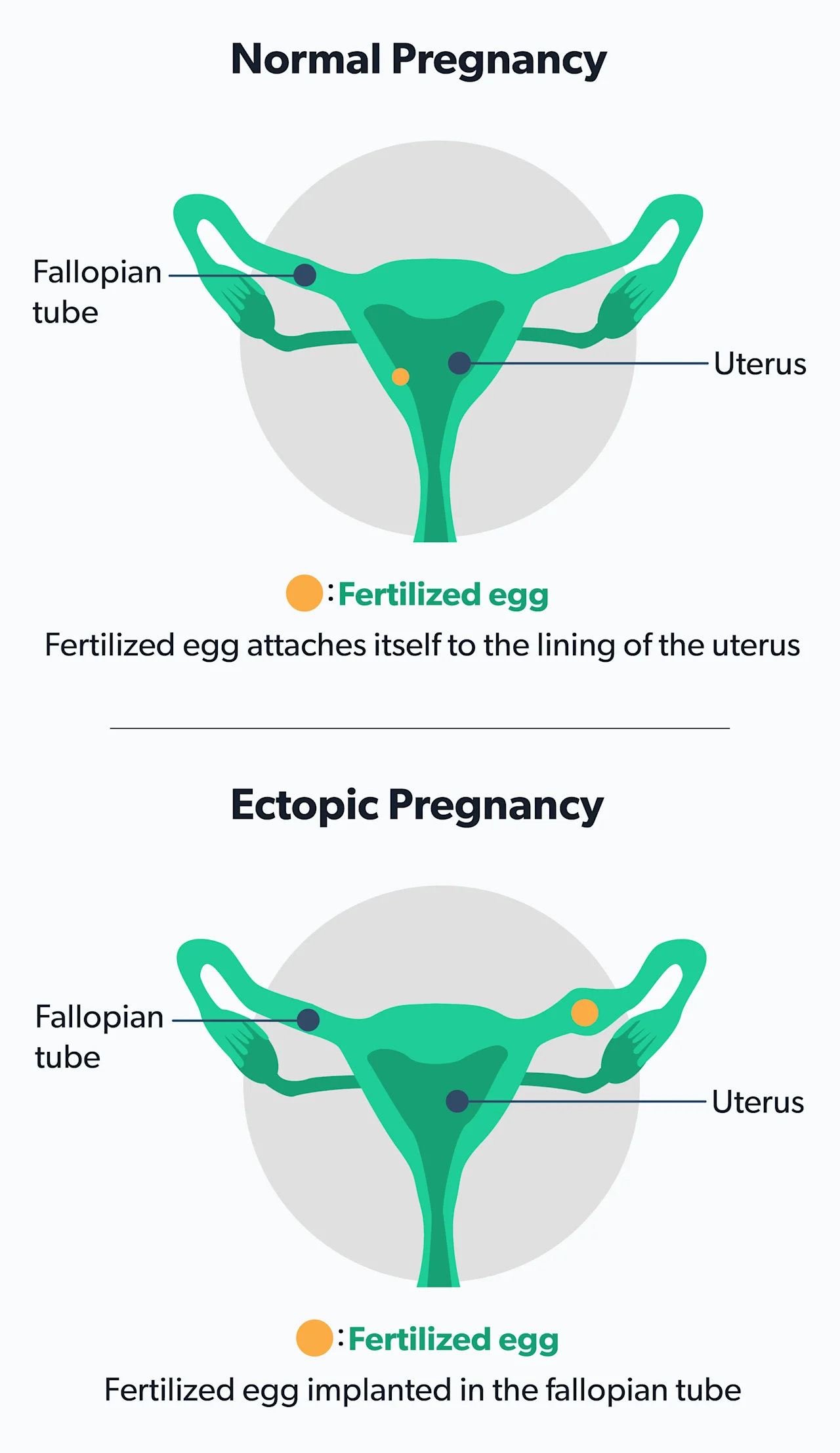

In biological females, chlamydia can spread from the cervix to the rest of the reproductive system, including the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. This causes a condition called pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which is associated with pelvic pain and abdominal pain; PID may also be asymptomatic. PID can lead to severe complications, including scarring of the fallopian tubes, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy (Hsu, 2019-b).

An ectopic pregnancy is a pregnancy in which the egg implants somewhere other than the uterus. Ectopic pregnancies can potentially lead to a rupture, which is a medical emergency and can even be fatal (Hsu, 2019-b).

While PID may also occur from a gonorrhea infection, the complications of PID occur more frequently when caused by chlamydia. This makes chlamydia and gonorrhea two important causes of preventable infertility amongst women. If already pregnant, chlamydia can increase the risk of having a preterm delivery (Hsu, 2019-b).

PID can also spread even higher in the abdomen, causing inflammation of the lining of the liver. This is called perihepatitis or Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome and can cause pain on the right side of the abdomen below the ribcage. As it advances, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis can cause scarring and adhesions in the abdomen, which may need to be removed with surgery (Hsu, 2019-b).

How is chlamydia diagnosed?

Diagnostic testing for chlamydia can be done either to confirm a diagnosis in somebody who has symptoms or as a screening test in somebody who does not have symptoms.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females under the age of 25. For those who are older than 25, screening is recommended in those who are at higher risk of infection (i.e., those who participate in high-risk sexual behavior such as unprotected sex and sex with multiple partners). It is recommended that MSM be screened at least annually, or more frequently if they are high-risk (USPSTF, 2021).

Multiple tests can be done to diagnose chlamydia, but the best option is the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). This is the test of choice because it is the most sensitive, which means it very easily detects chlamydia and will lead to the fewest false negatives (Hsu, 2019-b).

NAAT can be done once a sample is obtained. A urine sample or a vaginal swab can be obtained, depending on whether a patient has a penis or vagina. Individuals should also be swabbed everywhere they may be at risk of infection, which is determined by the type of sex the individual has. If an individual engages in oral sex and pharyngeal chlamydia is suspected, a throat swab should be obtained. Similarly, if an individual engages in receptive anal intercourse and rectal chlamydia is suspected, a rectal swab should be obtained (Hsu, 2019-b).

How is chlamydia treated?

Chlamydia can be easily treated with antibiotics. In some cases, you can start treatment even before the test results come back. This is especially likely if symptoms are present or if your sexual partner has tested positive for chlamydia.

Treatment involves one of two antibiotics: doxycycline or azithromycin. Both are generally considered first-line therapy for uncomplicated chlamydia. Azithromycin (brand name Zithromax) works after a one-time oral dose (pill). Alternatively, doxycycline (brand name Vibramycin) is used over a 7-day course.

If you have epididymitis, usually doxycycline is prescribed for a 10-day course. In the case of PID, you’ll need 14 days of treatment. Lastly, if LGV is suspected, doxycycline is prescribed for a 21-day course.

Azithromycin has the benefit of being a one-and-done treatment. But it can only be used for uncomplicated infections. Doxycycline can cause sensitivity to the sun (photosensitivity) so if you are taking doxycycline, make sure to wear sunscreen and do your best to avoid the sun while on the medication (Hsu, 2021).

Gonorrhea is frequently transmitted along with chlamydia. For this reason, many providers will also give a one-time injection to anyone with chlamydia. This injection is called ceftriaxone (brand name Rocephin), an antibiotic used to treat gonorrhea (Hsu, 2021).

If you are being treated for chlamydia, you should avoid having sex for seven days after starting antibiotics. The risk of getting infected again is high. If you have sex right away, you may continue to spread the disease and contribute to reinfection. With this in mind, you should also get re-tested after three months to make sure reinfection has not occurred. You should contact all of your sexual partners from within 60 days of symptom onset to let them know that they should be tested and treated as well (Hsu, 2021).

How can you prevent chlamydia?

The best way to prevent chlamydia is to abstain from sexual activity or to remain in a monogamous relationship with somebody who does not have chlamydia.

If you are going to participate in sexual activity, you should practice safe sex to avoid chlamydia infection. This involves using a polyurethane or latex condom or other barriers that entirely prevent direct contact during anal, oral, and vaginal sex. Keep in mind that just because something is a contraceptive does not mean it protects you against STIs. Birth control pills, spermicidal lubricants, and other incomplete barriers like the diaphragm do not protect against STIs.

Some people may take a medication known as Truvada for PrEP. PrEP stands for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and is taken by individuals who are HIV negative to prevent infection with HIV. Even though PrEP is effective at preventing HIV, it does not prevent other STIs like chlamydia.

Is there a vaccine for chlamydia?

Recently, a study was published regarding the phase 1 trial of a vaccine for chlamydia. A vaccine is a treatment that can be given to people that sensitizes their body to a certain disease. This helps protect against acquiring that specific disease in the future (Abraham, 2019).

Phase 1 trials are done in very small groups of people (in this case, 40 women). They assess whether or not the intervention is safe and what its side effects are. In this study, the potential vaccine for chlamydia was deemed safe and well-tolerated, which means it may move on to the next phase of a clinical trial (Abraham, 2019).

So what does this mean? For now, there is no vaccine for chlamydia. However, there may be one in the coming years if further clinical trials show it to be safe and effective.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Abraham, S., Juel, H. B., Bang, P., Cheeseman, H. M., Dohn, R. B., Cole, T., et al. (2019). Safety and immunogenicity of the chlamydia vaccine candidate CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes or aluminium hydroxide: a first-in-human, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 19 (10), 1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30279-8. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31416692/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021, Jan). Chlamydia - CDC fact sheet (detailed). Retrieved May 5, 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia-detailed.htm

Cunningham, S. D., Kerrigan, D. L., Jennings, J. M., & Ellen, J. M. (2009). Relationships between perceived STD-related stigma, STD-related shame and STD screening among a household sample of adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41 (4), 225–230. doi: 10.1363/4122509. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20444177/

de Vries, H., de Barbeyrac, B., de Vrieze, N., Viset, J. D., White, J. A., Vall-Mayans, M., et al. (2019). 2019 European guideline on the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 33 (10), 1821–1828. doi: 0.1111/jdv.15729. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31243838/

Hammerschlag, M.R. (2018). Chlamydia trachomatis infections in the newborn. In UptoDate . Weisman, L.E., Morven, S.E., and Armsby, C. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/chlamydia-trachomatis-infections-in-the-newborn

Hsu, K. (2019-a). Epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. In UpToDate . Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infections

Hsu, K. (2019-b). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. In UptoDate . Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infections

Hsu, K. (2021). Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. In UptoDate . Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infection

Mohseni M, Sung S, Takov V. (2021). Chlamydia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537286/

Pillay, J., Wingert, A., MacGregor, T., Gates, M., Vandermeer, B., & Hartling, L. (2021). Screening for chlamydia and/or gonorrhea in primary health care: systematic reviews on effectiveness and patient preferences. Systematic Reviews, 10 (1), 118. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01658-w. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33879251/

Taylor-Robinson, D. (2017). The discovery of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sexually Transmitted Infections , 93 , 10. Retrieved from https://sti.bmj.com/content/93/1/10

Torrone, E., Papp, J., Weinstock, H., & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014). Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14-39 years--United States, 2007-2012. MMWR, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63 (38), 834–838. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25254560/

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2021). Draft Recommendation Statement: Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Retrieved May 5, 2021 from https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/chlamydial-and-gonococcal-infections-screening